...NO ONE EVER WANTED BABIES TO CRY

It all started because no one ever wanted babies to cry. Which didn’t really make sense. They wanted this for myriad, variegated reasons. One of the least convincing reasons was that people were empathetic for the babies and didn’t want them to be sad: first of all, who is to say that when a baby cries, it’s because they’re sad? They could just be hungry, or so ecstatic that they don’t know how to deal with it, because they’re just a baby. Maybe they’ve only experienced placidity before that, and then got so excited, and so overjoyed, for some reason, that now they’re crying out of confusion. Confusion that’s not necessarily negative, and not necessarily sad. We also can’t say they, babies, are “sad” in the same way we say adults are sad. Adults—or even kids that are older than babies—are said to be “sad” when they are lonely, or when someone snubs them, or when they are in deep grief (over something). Maybe you’re just melancholic or depressed—“sad for no reason.” Maybe it’s existential or societal or “modernist malaise” or “modernist anomie” or something, probably. Babies probably don’t get sad like that—modernity hasn’t affected them yet, and they don’t understand—while attending parties—when they’re been snubbed. It doesn’t affect them; they don’t notice.

So we can cross empathy off the list, if we are to be reasonable. Unreasonably, you could say that you don’t want any baby to ever be uncomfortable or sad or “negative feeling” (or even “confused feeling”), ever. So that, if they ever cry, you need to get to the root of their crying and restore them to “neutral feeling,” or “positive feeling, but not a confusing degree,” status. This is a little absurd. We wouldn’t do this with adults—and if you did insist on holding the same prejudice against “feeling like crying” for adults as well as babies, I think it is fair to say that you are being unreasonable. There are going to be “feeling like crying,” or even “sad” or “negative,” things in everyone’s lives, and you have to deal with it. If you try to avoid it—it’s trite, so I’m not going to go too in depth or cite any sources or worry about phrasing it “not clunkily”—you probably would have “not sad” or “positive” or “not feeling like crying, and feeling like smiling instead” feelings either. You would just always be neutral. (I am going to refrain from commenting on whether positive feelings require negative feelings, or perhaps vice versa, in order to exist or be defined. Perhaps one could live in a state of constant glee—in fact, some say that this is why babies cry, because they lived in this state, and this state was the womb. Who knows. But in any case, such a state is probably inaccessible to the experiencing subject of a life.)

More realistically, people probably didn’t want babies to cry because it’s really loud and annoying. “Stop that,” they think, when they hear babies crying. “It’s really loud and annoying.” This is a more realistic and reasonable reason for not wanting babies to cry. That being said, think about the effects of acting on that eminently reasonable impulse (to stop the baby from crying). In the short-term, you will be happy, because perhaps, in your desire to stop the baby from crying, you give it some milk or you spin its mobile above its crib to distract it, or something, and you manage to stop it from crying. But short-term satisfaction usually comes at the cost of its long-term cousin; this is the principle of delayed gratification. Let us again compare the baby and the adult. If an adult is crying—well, first of all, they do it much more silently, usually, and less annoyingly—again, we don’t take pains to arrest them in their crying—no one would do that. So why is it different with a baby? Also, if an adult is crying, let’s say, because they want milk, we would probably be a little annoyed (though in a different, more subtle, agèd way than we are with loud babies’ crying)—we would think, “Why don’t they go and get some milk? Do they need it brought to them? How bourgeois.” It’s a little obnoxious to expect people, as an adult, to attend on you and bring you milk when you want milk. Even for rich people who can afford servants (or, “household help,” to “employ” a euphemism), this would be a little gauche: they would ring their servants, and ask for milk, and the servant would think, “Really?”

If the adult is a young adult, or maybe just a kid who is older than a baby, and they are crying, we would think it better to delay our gratification—to not just give in to the crying older-than-baby’s desire, or try to comfort them, perhaps spuriously, out of some sort of “duty” to empathy—and instead, proverbially, “teach a man to fish,” by letting them deal with their sadness by themselves, so that they don’t learn to rely on other people every time they have an unfulfilled desire or a malaise or an anomie, and to be self-sufficient instead. This is what I mean by delayed gratification. Instead of succumbing to empathy and getting that short-term satisfaction of having mollified the crying older-than-baby person, we delay our gratification, and derive the long-term satisfaction of seeing them “learn to fish,” and become self-sufficient: get their own milk, deal with malaise or anomie without being spuriously, but momentarily, comforted.

But for some reason, with babies, we throw these standard out the window—we throw the proverbial “baby,” of our standards and values, out with the proverbial “bathwater,” which in this case is a literal baby.

This is the question: do we want our babies to grow into “older-than-babies” with an ingrained belief that if they yell and scream, they will be satisfied? Or do we want to prepare them for the life of the adult, where crying and screaming will not, and should not, coerce those around them into satisfying whatever desire or negative-desire (“I want to not be malaised/anomied”) it is that is leading them to cry and scream. They have to deal with it themselves, and their moments of grief should be private, and brief.

It’s not “cold”; it’s just “fine.” Stop verbalizing everything; it’s annoying.

Clearly, responding to every whimful cry of the baby was a specious proposition. Very specious. But not even specious—“specious” means that on the surface it seems to hold water. But as I have just cursorily run through above, we see that the presuppositions of such a proposition dissolve under even the most cursory, surface-level run-through. You don’t need to go that deep. It’s not specious, it’s just absurd. It’s dogma, past a certain point. It’s illegally ill-thought-out and ineffective and inefficient. We’re not starting out our babies with the right tools for life in so doing. We’re teaching them to verbalize everything and be annoying.

That’s why we figured out if you just stop attending to them, eventually the babies will just stop crying. You feed them four or five times a day, nothing overkill. As many times as you would otherwise; you just leave them be for the rest of the time. Maybe you hang out with them, play with them, but if they start crying, just leave. Come back when they’ve stopped and then you can resume hanging out with them or playing with them. Eventually the babies will just stop crying.

It was a small, in a certain sense, societal change that had a major, oversized impact. It’s not that big of a deal, ergo “small,” to not attend to a crying baby. You don’t even have to move, physically. You can just keep on doing what you were doing before the baby started crying. You might have to change rooms if you’re in the same room as the baby or in a room nearby, just because the baby is really loud and annoying. But changing rooms is a small change. If you live in a small apartment you might have to go for a walk or go to a cafe. Not that big of a deal, a pretty small change. But in the grand scheme of things, you’re teaching the baby a valuable, ergo “big,” lesson. It doesn’t understand anything one way or the other, so it’s not learning anything, but you are teaching something. “Is it a big change emotionally?,” you might ask. No, not really. As I’ve cursorily run through above, the emotions involved in attending to a crying baby don’t really make that much sense. Everybody cries, so why is it imperative to make sure this subset of “bodies” never does? Is that empathy, or is a baby’s crying just really loud and really annoying? Really, you really just have to ask yourself that. Logically, it’s not that big of a step, or change, in thinking. You can be just as “emotional” about not attending to a crying baby, too, as you can about attending to it, by the way.

But even if you were attended to, when crying, as a baby, when you grow up, you are no longer a baby, and it doesn’t really make sense to continue to abstain from learning that lesson anyway. There’s really no excuse.

The one bad part is that it’s really annoying in your apartment if someone has a baby in the building, or just walking around and hearing all the babies crying. Those are the ones that haven’t learned yet and haven’t just stopped crying. They’re the new babies. When you walk around outside you hear babies crying inconsolably more often. But the alternative is having a world-nation of people putting their own needs ahead of others and pretending they’re being empathetic; and of people—older-than-baby people—who cry and scream until they get what they want, because that’s what they were taught. Or weren’t taught. They just kept being given fish instead of being taught how to fish. They were thrown out of a ten-story building with the standard and ideals and values of society. They were the bathwater of the procrastinatory bubble-bath you took instead of doing what needed to be done.

There is a problem; these are the facts at hand. It really is that simple. It always is. Is there a problem? There is a problem. Let us lay out the facts at hand. These are the facts at hand. Now we decide what is to be done. It’s that simple. Usually you just find out it’s actually not a problem, and is actually just not a big deal. It’s never really that big of a deal.

Everyone started listening to acoustic and piano covers to pop music. They said it relaxes them. Sometimes it was just acoustic guitar and sometimes it was just piano, but sometimes it was both. It’s always covers of pop songs.

People who liked experimental music now just listened to the sound of rain falling. They didn’t listen to the pop songs. They listened to “found sound,” with the sound of rain being that which was “found.” “I’m so glad someone found this sound,” they would say. Either that or they’d listen to field recordings, also of rain falling. There was also, for the experimental crowd, musique concrète, which juxtaposed field recordings and found sound—of rain falling.

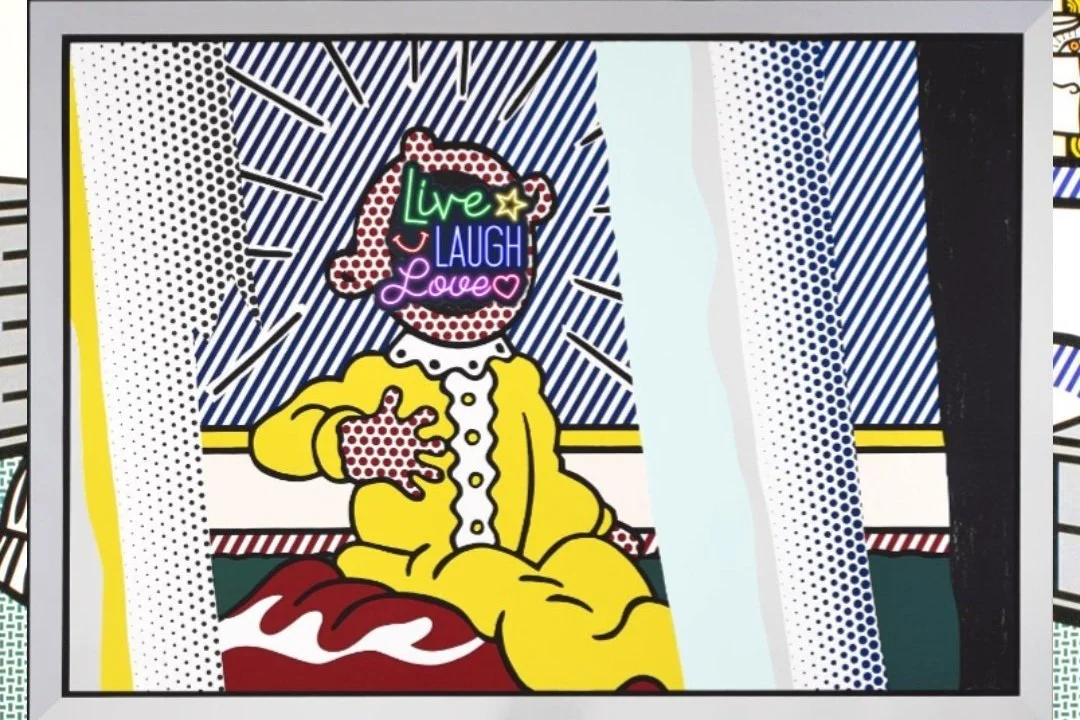

Everyone used to be verbalizing everything and being annoying. “Live, laugh, love,” they said, and then they said, “That’s a philosophy, and a worldview, for living. For living but also for laughing and for loving.” They lived by the same vague and vapid and vacuous sloganeering of signs adorning the wall of a Middle American coffee-shop somewhere in Middle America. “I’m thirty, flirty, and thriving,” they said. Everyone else thought, “You’re very annoying. Stop verbalizing everything.” They decided to “Live, laugh, love,” and they went from there. It wasn’t determined very effectively; they determined their philosophy from the wrong direction and tried to match their life to the philosophy, instead of the other way around. And it wasn’t even a very good philosophy, it was just a slogan from a sign on the wall of a coffee shop that they thought sounded nice and “ideal.” But it really wasn’t that ideal. It was illegally unideal. It was just kind of annoying.

Even the people who said that probably also thought that it was annoying, but they didn’t realize why they were annoyed, because they weren’t thinking and they weren’t looking at the facts at hand. So they sublimated their annoyance into being cognizant of variegated problems and verbalizing about those problems. There were lots of problems and people were vigilantly cognizant of them. “There are lots of problems,” they might say. The facts at hand were just taken for granted and never consulted. Instead, everyone tried to invent new solutions. They would be talking about some individual problem in particular, and they’d say, “Why don’t we just solve that problem?”, and then they’d create a task force to instate a solution. For every problem, there was a potential solution that was very hard to implement and a task force which litigated how best to implement the solution. Oftentimes, though, the problem actually wasn’t that big of deal in the first place, and the solution would just create more problems which in turn required more task forces and more litigatory efforts. They were all really cognizant of the problem at hand but everything that existed already existed and thus was infinite and infallible, in their minds, so they always decided they had to add a new element to the matrix instead of rearranging and reconfiguring the facts of the matter at hand. The matrix just became really crowded with elements but was still growing, and bulging, but then they just made the matrix bigger. They were excited when the matrix was bulging because that was a problem they could litigate and solve by expanding the matrix, and it gave everyone something to do. They’d say, “We have so much to do in the matrix, that we should expand the matrix first, and then we’ll be able to check that off our list and it will feel good to check something off our list, and the satisfaction of being effective and of checking a discrete task of our list will encourage us to do more of the other stuff we still have to do, and the other problems we still have to do, and to solve.” There were a lot of repeats and redundancies in the matrix. It was all really illegally inefficient.

Every time there was a problem people would verbalize about it. That was the preliminary stage, and then they moved on to litigation, which is still verbalization, but just of a special case. Then after that, the problem was solved and everybody would talk about it and throw an event for it where there were speeches about it and people used it as an ice-breaker when they mingled. Of course, the problem usually wasn’t solved, but instead it just had a new component to it now, installed on top of the problem, labeled “solution,” that usually just involved verbalizing how the problem was solved, but how you should remain cognizant of the problem and of the new component of the problem which was the solution. It was very important to always be vigilantly cognizant, and your cognizant wasn’t considered very vigilant, or at least wasn’t considered vigilant enough, unless you verbalized it. If a problem came up in a conversation, perhaps as an ice-breaker, it was very tactful to say, “I am cognizant of that, yes,” and that would “break the ice,” and it wasn’t very tactful to say, “—.” People would look askance at you if you just said “—,” and they might consider you incognizant and thus ethically-deranged, or, elsewise, cognizant, but not cognizant vigilantly enough—and thus much, much worsely ethically-deranged. If you said, “But it’s not really solved”—the problem—“it’s still there, it just has a new component installed on it”—first of all, that would be really bad, and tactless. But also, someone would probably just retort, “The real solution is to be cognizant of the problem, and talking about it is almost just as good as literally solving it. Not talking about it would be tactless, and bad. At least we’re doing something. Would you rather we just don’t talk about it? That would basically be repressing it, and then it would be sublimated into a sexual perversity, maybe even a sadistic one that would hurt people for sexual purposes. That would be really bad, and not good. Would you rather we all turn into sadistic perverts, who want to hurt people, just to get off? Or maybe you’d rather we do nothing?” They would probably say something to this effect. They would probably call you a nihilist, or a reactionary nihilist. Then they would say, “Live, laugh, love,” or, “I’m thirty, flirty, and thriving.” That’s how all problems used to be treated. It was really annoying. Everyone was really cognizant and it was really important for everyone to really care about stuff, things. And it was also really important to be flirty and thriving, be one thirty years of age; and also to be living, laughing, loving, but that was at any age.

People were always really annoyed. People were always pissed. That was one of the problems. “People are always pissed,” people would say. “That’s one of the problems.” Then they’d keep talking about it. Eventually they’d say, “People are always pissed because there are so many problems,” and that was the solution. Some people were pissed because it was all really annoying. “Those people are pissed because they’re really ethically-deranged.” Those people just pretty much stopped talking because they were too annoyed and they didn’t really care. They didn’t want to bother.

But eventually those people took power. They decided they wanted to bother. They ran touting the slogan of the “Silent Majority,” which was short for, “The Silent Majority That Is Really Annoyed, And Really Pissed.” People said that they were reactionaries. People said that they were nihilists. “You’re all reactionaries. You’re nihilists,” they said. Then the other people said, “You’re really annoying.” Then they said, “That’s not a response to what we said; that was a non sequitur, and an ad hominem attack.” Then they said, “No: because you said I was a nihilist, and a nihilist is someone who doesn’t care about anything. I care about that you’re really annoying.” They ran for office and they won and they took power. It didn’t really matter; it didn’t affect anyone’s actual lives. It was just a new president and a new political party that was in power. Then they instantiated the rule about attending to crying babies, or rather, about not attending to crying babies. It was politically imperative, they said: “This is politically imperative. The alternative is illegally inefficient, and just doesn’t make sense.” Eventually all the babies in the world stopped crying. It didn’t take that long, just a couple of months—for the individual babies, but also just in general. Pretty soon no one was crying and after a generation older-than-baby people didn’t verbalize and be annoying as much. Some still did, but now they were the minority—“The Not Silent, And Very Verbalizing, Minority.” And then of course new babies still cried, or at least as a rule most of them did, because there was a crying impulse at birth. Perhaps some babies are born and they already don’t cry. That’s besides the point. That’s why it’s still so loud on the street, or in your apartment if someone in your apartment has a new baby: from all the new babies that still had the crying impulse. There were always new babies; it was because people were always having babies. They balanced out the population from all the other people, who got old and died, or who otherwise died of other causes, like getting hit by a bus, or by killing themselves. Also, some people just didn’t follow the political imperative. No one really cared. It’s literally impossible to go door-to-door making sure everyone’s doing it (not attending to their crying babies). That would be absurd. So some people just kept doing it (attending to their crying babies). That just meant they cried for longer than other babies and maybe threw temper tantrums as toddlers and also as children. But sometimes they didn’t even do that. Then they would grow older and they were usually normal, upstanding citizens. It doesn’t really matter if a couple people don’t do it, or even if no one does it exactly to the letter, as long as a certain general atmosphere is established.

Things became very efficient. We started looking at problems, then looking at the facts of the matter, and then deciding what to do, which was, as a rule, very simple and straight-forward. We didn’t just scream and cry, and verbalize and be annoying, about it. For example, if the problem is that you want milk, then you would determine whether you had milk in your fridge, and whether it had gone bad yet, or not. Then you would go to the store for milk if either of the answer to either of those “whethers” was “No.” Then the problem was solved. Sometimes people realized that they actually didn’t want milk and that they wanted seltzer. Then they got seltzer instead. Sometimes people realized that they either wanted milk or seltzer, but no milk or seltzer existed on the face of the Earth. Then they were forced to conclude that it was relatively useless to want milk or seltzer, and that they shouldn’t care, and then there was no more problem. For bigger problems, it was still that easy, and simple, and straight-forward, but just at a bigger scale.

The first big problem everyone really cared about was the problem of climate change. The facts of the matter, though, was that everything was fine. People realized there wasn’t really a problem. The facts of the matter included that the sea level was rising. “OK,” everyone said, “That only affects people and animals who live by the ocean, and also plants and animals that live inside of the ocean (since the ocean is getting warmer and that might affect them).” Since everyone was people, they decided to only focus on the people part. The people who lived by the ocean decided that they should move. Littoral housing was declared illegally inefficient. Then someone said, “What if there’s so much water that if it all melts and the oceans rise to the maximal degree there’s no more land to live on.” Then someone calculated it and there wasn’t that much water. “But if I’m wrong,” they said, “then we can just live in submarines and keep all our food in submarines and otherwise just eat fish—the ones that can stand to live in warmer water, or that evolve to be able to do so. We can fish for them from our submarines.” That was reasonable and so people stopped worrying about it. “What if all the fish die,” someone asked. “Then I guess we will die. But who cares. It doesn’t matter.” That was a good point too. The Earth couldn’t die—the Earth isn’t alive. The only negative repercussions of climate change were the negative repercussions that affected human beings. Animals didn’t care if they died; they didn’t stress about it, either they died or they didn’t. It just made things harder for people, because people like to go on hikes and things, and to live littorally. But if the Earth becomes inhospitable, then you just die. There’s no alternative. You can’t live in an inhospitable place that wants you to die, and wants to kill you. If people are causing climate change, and if people’s actions are what is making the Earth inhospitable, then you should stop doing those actions—but that’s only if you care if you die. Also, if you pave over the ocean with concrete, then rising ocean levels won’t affect you. And then you won’t die and you can just live inside if the ozone erodes completely so that you won’t get burned. Or, something prevents you from paving over the ocean or living completely inside, or that doesn’t work for some reason, and then you just die. People like to go on hikes and things, and to live littorally, but if you die, you don’t.

The next big problem everyone really cared about was the problem where no one could ever go into rivers. People were always saying, “A man cannot walk into the same river twice, because he is not the same man, and that is not the same river.” “No one can do anything in a river,” they would say. “No one can do anything.”

Conversely, starting with the proposition that no one can ever go into rivers, different people would say, in a sort of proof by contradiction, that “A man can step into the same river twice.” “That is the same river,” they would also say. “I think a man can do that; I think we can do things in rivers.” But, again, it wasn’t really that big of an issue. You didn’t ever have to go into rivers. No one was ever holding a gun to your head. In a river or otherwise. And even if they did—you can always just die.

“You can’t just die. You have to go into the river. No one can ever go into rivers, but you still have to.” But if you go into a river, someone holding a gun to your head is not a good excuse. Actually, it’s precisely that. An excuse. Qualifications or value-judgements of neither “good” nor “bad” obtain, since “excuse” just implies it wasn’t the real reason you went into the river.

But really big problems don’t really impact your life anyway. Most people didn’t really care.

Some people said: “There is a truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Truly serious philosophical problems are big, and they impact your life; a lot of people care about them.”

People would go to the Vessel in Midtown, at Hudson Yards, and jump off it. That was one of the problems. A lot of people would always be killing themselves. Usually they didn’t do it off the Vessel. And then other people would say, “That is a big, truly serious philosophical problem.” Other people, who didn’t kill themselves—or at least hadn’t yet—would read the headline in the news, “Someone killed themselves by jumping off the Vessel,” and they would say, “It’s almost too on the nose that people are using a garish piece of pseudo corporate ‘art’ that’s in the middle of a massive gentrifying real estate project, to express how deeply society has failed them.” But is it really possible to draw a clean correlation between a suicide, and the reason? Or really, come to think of it, any clean, expressible-in-neat, tidy language, reason, that anyone does anything? Especially not something so drastic, or so eventful (as in, an action that is “full,” with the quality of being an “event”), as suicide. Even if the guy who killed himself said his explanation for killing himself was that “Society has failed me,” I don’t think anyone would really believe him. People can say anything, or cite any justification for anything, and we rarely believe them, especially if their explanation for doing something is very abstract and makes explicit comment on “society” or some other quite large, abstract concept. If I killed someone else, and said, I did it because society has failed me, no one would say that it was “right on the nose” and also a good point. They would be embarrassed for me that I thought people would believe that explanation. They would probably feel really uncomfortable around me because I was clearly kind of unstable and violent. But for some reason, if someone else points at me, and says, Society has failed them, then you might say, “OK.” But you would still feel really uncomfortable around me—the explanation, at bottom, wouldn’t carry much weight. Explaining things, and coming up with excuses, are genuinely very stupid things to do.

Another problem was health care: people would say, “I’m really depressed; I really want to kill myself”; but then they’d also say, “I really want health care”—presumably, so that they could live, and be medically attended to (via health care) so as not to die. None of it really made very much sense.

Ironically, most of the people who said that society had failed people who jumped off the Vessel or otherwise killed themselves, didn’t actually kill themselves, even though they lived in the same society. But even if they did, it’s more telling that they were already looking for an explanation for why they were going to kill themselves, than whatever the actual content of said explanation might be. If we have a “big problem,” or a problem with “the world” or with “life,” what people actually mean, what is actually being said (their speaking of “big problems” and “the world” or “life,” an unconscious cry for help), is that they have a problem, literally, with thinking about things in terms of empty concepts such as “the world” and “big problems” and “life” instead of what is actually happening in front of their face. Now, that actually is a big problem—“big,” rightly speaking. It is a big problem that someone is being that stupid, because they will likely just go on creating new problems for them and their breed to pretend and play games about—new, actual problems, that will impact what is front of everyone’s faces, like the problem of someone being annoying, and also being in front of your face.

You also have to ask what someone means, what they’re really trying to talk about, when you talk about “the world” as such. For example, when you say “the universe,” what you really mean is the observable universe; and when you talk about that, all you could possibly really mean to say is the galaxy—our galaxy, the Milky Way—because what the hell could you even really say about anywhere else?—ditto for when you talk about “the galaxy”—what else could you mean, but “the solar system,” our solar system—and so on, until you get to “the world.” When you talk about “the world,” what you’re really talking about isn’t the world “as such” after all—the whole compendious sweep of it—no, you’re talking about the world of the affairs that surround you, that all involve you, too, in their own minimal, every-man-a-king, every-vote-counts sort of way; and thus, extending from that, probably all the other places and various “worlds” that interact with that world—so all of this is probably what you mean to include when you toss off a phrase like that, “the world.” When you really get down to the bottom of it, “the world” you’re referring to is nothing so grandiose as the world of experience, intimate experience, eminently personal experience; not even “the world” of bodily sensation, or personal, physical presence but “the world” of the processes and mechanisms and machinations by which we think about the world, “the world” by which and in how we structure and formulate and understand the world as “the world,” even in the sense of “the world” as is commonly understood and how we rightly expect others to take it when we say “the world”; and all of us are going around throwing around the exact same expression, The world!, The world!—and when pressed, all of us’ll even cop to the very same definition, “the world,” the globe, Earth, the continents, Pangea, et cetera and et cetera—even metaphorically-extended, the very same definition: the general sphere of things, social affairs and customs and current events and people as they interact on the globe, on Earth, et cetera—but when you really get down to it, all of us are all experiencing, and thus talking about, just as many “the world”s as there are us upon, objectively-speaking, the world as such.

What is “society”? Is society in the room with us right now? What is “life”? Can you see it? If a baby is crying, is “life” that the baby is crying or is life that you can hear it?

Most big problems don’t really impact your life. They’re not even “big”; they’re actually small—so small they can dance on the head of a pin. Most big problems don’t really impact your life. Most people have never really cared.

No one ever wanted babies to cry. But babies do indeed cry; admittedly, it would be nice if they didn’t, but they always seem to. And even when they don’t—which is very rare—it’s usually because they are mute, or are otherwise afflicted with some variety of vocal-cord issue; or, because they accidentally died. If you die, then you don’t cry anymore. So in that case the problem is a lot bigger than worrying that your kid is crying. But just because you have a problem does not necessarily mean, excuse the fact, that you care; one can imagine a person whose baby dies, and they do not care. If the baby is dead, and will remain so, in either scenario, what difference would it possibly make—why would you spuriously, and often quite self-righteously claim it to be “cold,” “not fine”—that one person refrains from caring (while the other cares, and makes eminently known to others their “care”)? It’s weird to consider it a virtue just to care, when caring won’t bring your baby back. Even if you do care, at first, it’s also irrefragable that eventually you will no longer care, even if it takes til you’re dead. If you die, then you don’t cry anymore, but incidentally, you will also cease to be bothered by crying. But before then, you can always just choose not to care; at any given moment the choice will be available to you. No one is holding a gun to your head—at any given moment, you don’t have to be a baby. At any given moment, you can either deal with the issue at hand, taking into account as effectively as you can the facts of the matter, or you can forgo doing so—you can kill yourself. You can live, or you can die. Sometimes, even if you opt to live, you will just die anyway; but it’s nothing to cry about. Both options are honestly fine.

Actually, perhaps the only (properly speaking) un-“fine,” not to mention illegally un-valiant, option, would be, opting to live, all the while squirming like an undeveloped and undeveloping infant, the drunken tail that wags the dog—variously begging those around you to hold guns to your head, and blaming them for never pulling the trigger; putting music on in the background, and then crying to drown it out.

To die, slowly, at the pace of life.

by Peter Schutz