THE SHIMAMURA INCIDENT

“Many men are not born. They are manufactured. They might become men, but are made artificial.”

He said this as he looked right past me.

I was locked into a dying ember, draining ash from an incense tower and he was looking out of the window with his eyes lurching upwards toward indigo lakeland. A 3D printer howled like a banshee in the corner of the one room apartment. In strands, hot plastic rendered the bone pale frame of a machine developing a machine developing a machine. We were waiting for the next stage of history. The future smelled like burning plastic. The countryside rich in animal shit fought against the future.

I asked him what he meant by that. “Conceptually I knew they would take two years of my life. You do the math every which way when you’re about to serve a sentence. And what tortured me the most was the fact that it’s two Summers, two Winters, Springs and Falls all billed to a cage.” As he was speaking, the young man sitting across from me had an unsuspicious look about him. I couldn’t recognize anything criminal about him, a fault of mine that the Kyoto police had no problem overcoming. If he looked like someone’s dad, that’s because he was. Shimamura said no pictures and no recordings, but I could take notes. To my own embarrassment the whole interview was conducted in one language because his English was nearly as good as my own. During a conversational test-run my Japanese shivered.

“If you want to hear about a true crime, my girl was nine months pregnant and she gave birth the night I got put away. In Kyoto. where we were living, my sister contacted me in the evening saying that Mizuki was going into labor. She told me on the phone that cops were waiting for me outside of the emergency room. They knew where to look. But Yukiko told me on the phone what room on the seventh floor she was preparing to give birth in. Believe it or not I had to sneak up into the oncology ward and watch Mizuki give birth to my child from a window across the street. It was perverted.”

Shimamura lowered his gaze and pinched the pale skin in between his brow. The somber story climaxed with his vision of his baby’s blood burnished crown. He described to me in detail how a human baby bloomed from his girlfriend’s womb. I’ll never forget his face as he described his newborn daughter sipping air, the coldness of her first breath stunning her little lungs.

He said. “I was crying, and I could not tell if it was the rain or tears flooding the view through my binoculars. At that moment a nurse came into the room and I had to hide them under my coat. He thought I heard bad news. Poor guy was hugging me because he thought I had been diagnosed with cancer, and part of me felt like I had.” Shimamura started laughing while he torched a cigarette, adding to the myriad of smells crowding the room.

“And then after that you went to prison?” I asked. My question shifted his emotion. He looked out of his curtains like that famous photo of Malcolm X, preparing to defend his home to the death.

“Not immediately.” He looked back at me with a paranoid glare. “I had a gift prepared for our baby because I knew Mizuki would be going into labor at any time.” Shimamura recalled driving home with one last thing to do. He could remember his truck tires churning through a tricolored deluge, the crimson rain droplets splitting hard, briefly bouncing up on the road like wheat fields, regenerating into protean blades of grass. “I pulled up to our home very carefully, without a second thought of how quickly risk had lost its grim patina. There on the porch I left a plush lamb, a gift from her father, which would be my daughter’s first worldly possession. You can’t imagine my reluctance when I sat down on the stoop and called the police on myself. Court was quick and I plead guilty to expedite a surprisingly light sentence of only two years, or 730 days. Or 17,150 hours. My only hope at the time was to get home before my daughter had any recollection of me being gone.”

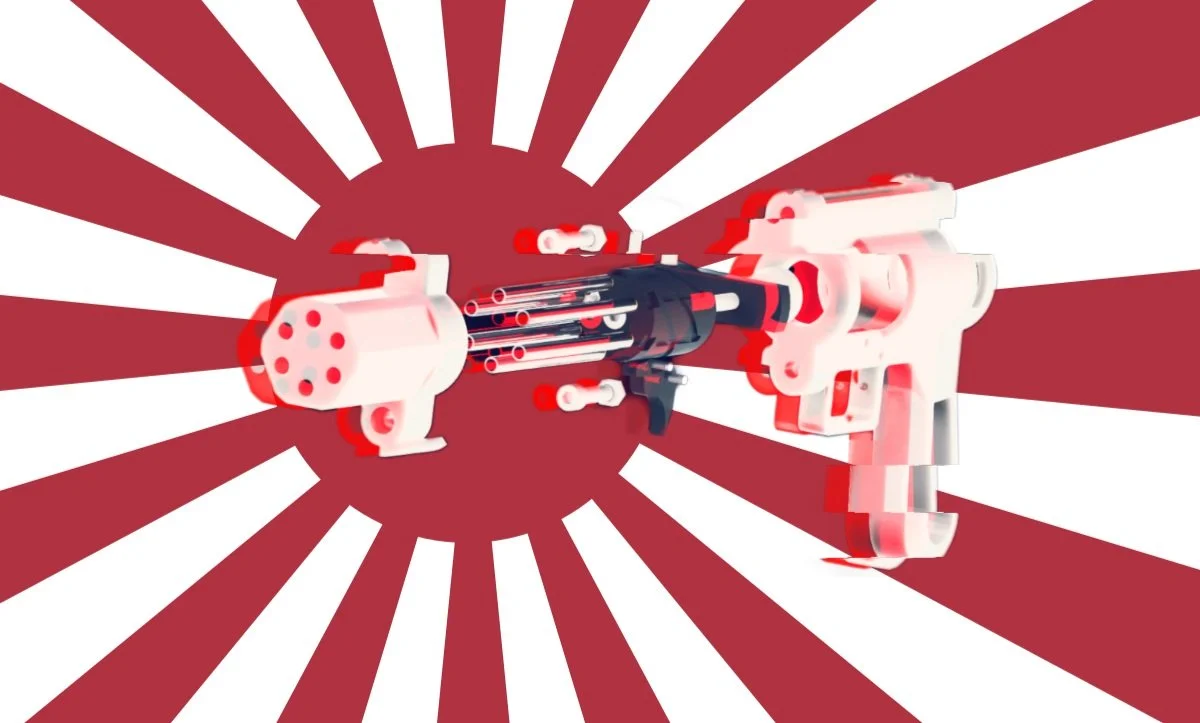

Shimamura turned to the machine. Watching a 3D printer create an object is in many ways like nothing you’ve seen before. If you watched carefully a weapon was spaghettified out of hot wax using pure math, then collected articulately on a printing tray.

The first piece was coming together. The pistol barrel was oddly shaped though efficiently produced. He stood up to shuck the thumb sized cylinder off the printing platform and launched it hot potato at me. I looked through a bullet sized peephole at its creator, who leaned over his laptop spamming orders. The 3D printer came back to life.

“Did you ever go to jail before Andrew?” He asked me.

“Do I look like it?”

“I can’t say so, but neither do a lot of people.” The printer began churning out the next firearm. “I didn’t even know at the time that it was illegal to print guns. But I don’t think anyone did. It’s a strange feeling going to prison for something nobody knew was possible.” He sat back down. There was a brief lull in the conversation, Shimamura didn’t like talking about jail so he had to gather himself for the questions I didn’t have the nerve to ask. “I think that’s part of the point.”

He continued. “My cell had a little window to the outside world. From one porthole foodstuffs were delivered to my cell by guards. On the opposite side my true nourishment was delivered.” Shimamura tried to describe the plexiglass from which he went window shopping for shimmering jewels. “A malnourished cat might scurry by to lay its tongue upon a morsel of food left from my dinner. Sometimes a songbird might land on the concrete outcropping. I’d listen for laughing school children walking by the prison in the morning. All these details I collected became worlds full of temptation that helped me escape monotony induced dementia. And all these little gems became further fuel for dreams. Sadly I got very good at dreaming.” In prison there was an acrid cagey stench meshed into every vision and his mattress became a derelict vehicle piloted by sleep.

“I felt my life, something that I should have had an entire recollection of, slipping away into an already abandoned future. One day I thought fuck it. I was just gonna kill myself, not for some seven lives for my country nonsense. This wasn’t political anymore. I didn’t believe in that. I didn’t care about my country or human rights, or for any of the theory that I’d impassioned myself with once. Even less, I couldn’t be bothered to go on as a scapegoat. I didn’t even care about guns anymore or other people. The cynical part in me thought people didn’t deserve them anyway.” He said.

“It’s sad to hear you say that because the gun printers lauded you, they said you performed your work without fear or dishonor. But you make it seem like the sacrifice was totally in vain.” As I finished my sentence a contemplative smirk dialed up his ears.

“The really funny thing is I learned more about freedom from inside a cell than I ever could’ve anywhere else in the world.” He paused to check on the printer. “At my most idealistic I always believed that human beings did not need to be taught the meaning of freedom. I saw the firearm as an opportunity for radical equality. Quite simply, the firearm is a humanism. I believed that because the human being is too precious to be left undefended.”

“A lot of people just saw you as selfish, putting your politics before the safety of others. You were treated like a terrorist. Like you were already an assailant.”

“Yes I’ve heard that a thousand times before. What we don’t realize is that freedom itself is selfish. I saw the way I used the internet and I realized it was a mirror of who I really am. The way I see it, your search history is a history of you searching for who you really are. And sure one day someone will get killed by a 3D printed gun, it could even be me. I don’t care because it hasn’t happened yet but it will soon.” He picked up the bench scraper and chiseled off the Liberator’s pistol grip from another printer. “Of course there was a time during my sentence where I wished I never given birth to the Zig Zag revolver and that I could’ve spent time with my daughter. Naturally these are all selfish thoughts.”

He took a breath and continued. “When I wasn’t thinking about killing myself I was thinking about my daughter. At the time of my little epiphany it had been exactly one full year since I’d last seen her, which made it her first birthday. And that whole day was spent agonizing over the value of my own life, staring at her precious face enshrined on a wallet sized portrait. From the lamp lit ceiling, hallowed light shone through the transparent photo beatifying her. In that picture I’d never seen anything so self-righteous.”

Shimamura began scratching off excess ABS plastic to fit the receiver with the trigger group. “I realized that what I loved so much about my daughter was that she didn’t ask to be born. Babies don’t make requests, they make demands. Sitting in my cell I felt an ascetic rebellion stemming from the idea that existence possesses an instinctive will to creation. While reigning down the arrowy lamplight, I began to weep vengefully with an immense satisfaction in the knowledge that not even God could undo my creation. That night the tears streamed down the side of my cheeks, dampening my pillow case.” Inspiration came laced by a cruel inflection distilled in his voice.

Shimamura spoke, “I did not ask to be born, weak people always use that phrase as an excuse for their own shortcomings. Pardon the cliché but it’s true. I for one know that I did not negotiate. I know some fall victim to their own bodies. I, on the other hand, took my life as captive. My daughter’s birth reminded me how I leapt at the chance of a beating heart and how, in a nine month siege, my soul took my flesh prisoner.”

I looked at the man with awe as he handed me the Liberator pistol, fully manufactured. He continued speaking. “I had my ‘how’ and if everything went according to plan I would be free in one year’s time. No more jail. Only freedom. That’s what I thought to myself. I figured that as long as I had my own reasons I never needed to die.”

Ensnared in his eyes I said, “Tomorrow we shoot the 3D printable firearm.” Shimamura grinned back at me.

It was early. The man glides pale and thin onto our makeshift range. We meet in a lush backwoods, thirty minutes away from his home, quite out of the way. I watched Shimamura walk with a body purchased on borrowed time. I remember thinking to myself, “Was this one of the unsung bastards of history? The misfit who whistles a song as he throws caution to the wind. How many of him are there out there?” An overpopulated worldful.

Shimamura brought two different guns in a briefcase. One was his own Zig Zag revolver design and the other was the liberator single-shot pistol we printed last night. His Zig Zag snaps open. The damned dusk broke quick as if by whipped horses hauling freight. The revolver’s cylinder digests eight rounds, .22 rifle, built to buck death subsonic. I took aim with the gun and fired west. The bullet claps through a line of percolating oak fronds. He didn’t recommend a second firing.

On the other side of our make shift firing range a Buddhist shrine laid tomblike, bombed out in the war and never repaired. In the deep woods, Shimamura told me, old shrines deep in the countryside were built to remind people that plants and animals are one and the same. I saw the exploded shrine and saw in it a ceaseless grind towards an atomless world. Siddhartha was only partially correct. Shimamura, like Buddha, believed we will one day become sound, an Om, a rhythm, an equation, a pulse, and then we would become unregulated.

Next the Liberator. A forerunner of its kind, flecked in a sinewy plastic musculature. In the sunlight it glowed white-gold. Much of today’s 3D printing is done by a process of additive manufacturing, a process by which language births plastic through electric synapses. The frame, the barrel, the trigger group, all fizzled out of thin air into solid concepts.

“In 3D printing we have a word. Physible. A stage basking between brain spasms, between conception and creation, between thought and action. Physible, means a file, a computer language, a set of pulsing signals begging to be born, to be made tangible. In these gun files, I saw an idea in its platonic potency, I saw its form, and then I saw a gun in my hand. Then at once many prosthetic hands, sex toys, cars, sprinting through the ether in a raving shadowland. To me the 3D printer is an altar of unlimited information for which there is so much hope. From a single letter of code we could recreate the entire universe tomorrow.” He spoke, and I believed in every sound that came from his mouth.

It fired perfectly the first time. In reality, the Liberator might very well explode in your hand if you shoot it a second time. I thought it ironic that the weapon itself, in practicality, was so useless and yet the potential for history is so immense. Magnificent.

Shortly after my excursion to visit Japan’s first gun printer came to a close. I thanked Shimamura for the opportunity and we parted ways. It wasn’t long after that I went back home to Pittsburgh.

Two weeks later, the article went out to a chorus of mild intrigue in the 3D printing community. It was while I was on a walk overlooking the Allegheny that I stopped to look at the Pittsburgh skyline from a promontory. Already the world we knew was steadily rewriting itself into ones and zeroes. It was becoming a world burdened with so much information without origin. The Allegheny River with its darkling gloss intimidated me. The river was a road which spanned infinity. I knew they could never censor the firearm. No one could. My hope was that for the rest of time no one could strip life of its inherent danger, and that like Shimamura each one of us would become the usurpers of meaning. He helped me see that will power is measured in action.

And for the people who lament that they did not choose to be born, I wanted them to know that I chose the world and that we are on two sides of the same coin. We are on that fringe, change is coming, and soon even live birth will be a rarity. We will soon reach a tipping point and will be made to decide who we want to be.

by Kenan Meral

Kenan Meral is a short story writer working on a collection titled, ‘A Rash Impulse’. He is most strongly influenced by the literature and philosophy of Yukio Mishima.